Review: Nightcrawler, a fantastic rendering of capitalism

by Jen Izaakson

The Nightcrawler works as a contemporary insight into working conditions in the post-economic crisis West, one still reeling from the 2008 crash. Lou Bloom (Jake Gyellenhaal) relentlessly embodies all that is alienating about contemporary life. Lou casts a hollowed out figure onscreen, representing different positions within capitalist employment, shifting from lumpen criminal, exploited worker to exploiting boss.

The Nightcrawler works as a contemporary insight into working conditions in the post-economic crisis West, one still reeling from the 2008 crash. Lou Bloom (Jake Gyellenhaal) relentlessly embodies all that is alienating about contemporary life. Lou casts a hollowed out figure onscreen, representing different positions within capitalist employment, shifting from lumpen criminal, exploited worker to exploiting boss.

Spoiler alert from this point onwards

Lou Bloom steals copper and bicycles to survive. Even at this low societal rung Lou wholesale buys into the ‘positivity’ self-entrepreneurial meritocracy-myth mantra, that “hard work leads to success”, despite the Los Angeles around him appearing in ruins. At one point Lou offers to do manual labour in a skipyard for free, explaining to the owner, “lots of young people today are doing unpaid internships in the hope of full-time positions – I could start tonight?” The owner, having momentarily purchased Lou’s stolen copper, states he doesn’t employ thieves and Lou, without dejection, gives him the thumbs up, “that’s smart. Have a nice day!” McDonalds treatment.

Lou wears work clothes constantly, even at home, and solely speaks in a ‘managerial’ self-motivational style, peppering ordinary conversation with meaningless quips such as “to win the lottery, you have to buy a ticket”. In doing so Lou avoids all genuine human interaction with other characters and begins to take this distancing effect to its logical conclusion: treating other people as if they were objects of utility i.e commodity fetishism.

Lou acquires his first paycheque of the film from a television news station for up-close graphic footage of a dying stabbing victim. Filming the victim’s medical treatment by paramedics before police reprimand this is Lou’s first ‘scoop’ as other cameramen appear unwilling to venture near, either out of respect for the victim or the law. Lou’s willingness to equate human life and activity with money emerges as the central theme of Nightcrawler.

What’s news?

Lou begins a new regime of listening to internal police radio and attending any serious accidents or criminal incidents broadcast, but only in ‘rich white areas’, at the behest of Channel 6 News. The anchorwoman sets out the remit, “a shooting in Compton isn’t news. We want white. We want rich. We want violent crime in poor areas creeping into the suburbs”. The media developed narrative of poor black crime affecting those who can be rendered its ‘true victims’ is made explicit. Savvy Lou decides to ‘recruit’. He advertises online and meets Rick, played by UK Asian rapper Riz Ahmed, at a café. Rick is a younger man, who despite completing high school is homeless, unable to find permanent work and squatting in a garage. Lou tells him this is a ‘great opportunity’ (to work for nothing) to join his ‘company’ (that doesn’t exist) and that ‘we’ (just Lou) are happy to offer him a position without pay, to gain ‘valuable experience’ (making Lou money). After some haggling Lou agrees to pay Rick $30 a night, below the U.S minimum wage, from the several hundred he is receiving for each segment of footage sold to Channel 6.

The one relationship Bloom does willingly ‘invest’ in is an attempt at romance with Nina (Rene Russo), the aforementioned anchorwoman. After pressuring Nina into a date, Bloom explains how, “being alone has advantages. You have time to do the things you want, but there isn’t anyone to be with, beyond flirtation. That’s what I want with you”. Nina rebuffs these advances, citing Lou’s younger age and status as her colleague. Lou begins to ‘negotiate’ as if in a business meeting, calculating the ratings his footage has brought Nina’s news show.

The one relationship Bloom does willingly ‘invest’ in is an attempt at romance with Nina (Rene Russo), the aforementioned anchorwoman. After pressuring Nina into a date, Bloom explains how, “being alone has advantages. You have time to do the things you want, but there isn’t anyone to be with, beyond flirtation. That’s what I want with you”. Nina rebuffs these advances, citing Lou’s younger age and status as her colleague. Lou begins to ‘negotiate’ as if in a business meeting, calculating the ratings his footage has brought Nina’s news show.

Lou has mined the internet for information on Nina and, in classical male obsessive fashion, has acquired, “everything there is to know about you [Nina].” He threatens her with the fact that she has never had a media role longer than two years previously and that he could sell his product elsewhere. Lou’s seduction becomes a simple equation of transactionary products of exchange, “I have something you want and I want you”, both career ambition and sexual desire equated and emptied of any notions of consent or libidinal preference. Lou claims Nina has “a choice” (to sleep with Lou), but that he has “choices too” (to sell footage to competitors). The notion of ‘choice’ enters as a minor differentiation of unwanted options: unemployment or sex with Lou.

Nina only acquiesces to Lou’s sexual blackmail after he films a triple murder at a residence of a super-wealthy family. Lou names his price, telling Nina he wants $15000, an introduction all senior managers, the footage to be called ‘Property of Video News Coverage – A News Gathering Company’ (the made up name of Lou’s made up company) live on air and for her to “do all the things I want when we’re alone together”. This intrusion into a crime scene sparks police attention towards Lou. This is in contrast to a similar intrusion into a homicide in a working class neighborhood. There, Lou filmed the victims of a shooting and crossed a police line to capture events inside their home, but the police did not take an interest (it is only when the victims of Lou’s invasive behavior and violent crime happen to members of LA’s wealthy elite that they deem such an interference worthy their attention).

Haggling

Lou’s ability to bargain, be it over sex or paying Rick, who he repeatedly tells “has no leverage in this economic climate”, falls short with the black female police officer investigating, thereby casting the authorities as the ‘good guys’ in Nightcrawler. This is not itself symbolically significant, but the language used between the female Detective and Lou is. In the second to final scene Detective Fontieri shouts at Lou what has been the clear truth through out the film: “I don’t believe a single word you say. Every word you say is a lie”.

Lou’s ability to bargain, be it over sex or paying Rick, who he repeatedly tells “has no leverage in this economic climate”, falls short with the black female police officer investigating, thereby casting the authorities as the ‘good guys’ in Nightcrawler. This is not itself symbolically significant, but the language used between the female Detective and Lou is. In the second to final scene Detective Fontieri shouts at Lou what has been the clear truth through out the film: “I don’t believe a single word you say. Every word you say is a lie”.

Lou operates only within grids of unacknowledged deception/self-deception He is animated through routines of internalising outside constructs, in what Sartre termed ‘bad faith’. These supplant any subjective experience or psychic life with relations of employer/employee reproduced through out the film. These relations have offered Lou a way to navigate his economic situation, both through exploiting someone in a worse off material position (Rick) and using precarious job status to blackmail Nina.

Life message

The film ends with Lou rising to the status of ‘boss’ as he welcomes three unpaid interns to his ‘expanding empire’ of two vehicles (instead of one). This venture, driving around the city in hope of finding and filming for profit the worst scenes of violent crime and large-scale accidents, works as explicit metaphor for all work relations under capitalism: human suffering for profit as its basis.

Nightcrawler’s message of life for sale is clear, there is no escape from it, only alternating positions within it. There are those caught up in violence, there are those racing to capture that violence and package it for sale, and there those at home viewing that violence over breakfast.

Lou is declared a ‘winner’. He has becomes self-entrepreneurial and self-actualising within capitalism through a mode of ruthless self-regulation. To follow Lou Bloom, the penniless hopeful now ‘self-made’ company owner, it’s shown to repeatedly require the enactment of violence, exploitation and a simultaneous denial of that violence and exploitation, even of the self.

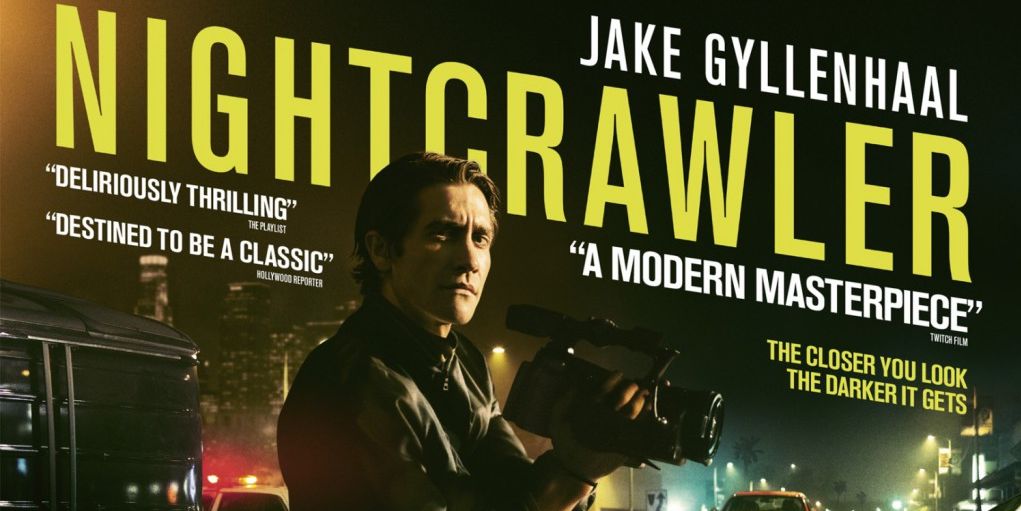

Lou is now a popular and well-known name at Channel 6, grinning at his follow ‘do wells’ and still never not being dressed for work. The layers of pretence, relying on ‘managerial speak’ and basic bullshitting do ‘pay off’ for Lou, but have ensured he is alienated from any true self he might have once had. Lou’s ego is near perfect introjection of market mechanisms and capitalist logic. Any authenticity eroded, Lou subsumes himself in a denial of human interaction that might exist outside of commodities. Jake Gyllenhaal, a man greatly admitted for his looks, is, as Lou, depleted of all beauty: dark-eyed, gaunt, greasy haired, skulking sullenly at night, ready to transform his face from non-expression to plastered grimace when required.

Lou is a poor actor playing at being human, all lifeforce somehow pressed out of him. In many scenes Lou resembles a corpse, a dead man who once lived long ago. In his new life after death Lou’s living relies on lying to his most recent dupes, those unpaid interns. Individuals ‘given the opportunity’ to be lured into risking their lives to make Lou rich for free, chasing a hope to one day be in his position and receipt of capital. The soulless dead leading the dying. For all of these exhibitions of relations Nightcrawler is a fantastic rendering of capitalism in the current moment.

Pingback: Review: Nightcrawler, a fantastic rendering of capitalism | Jen Izaakson